UK Airports 2023 Passenger Recovery vs 2019

In 2023, only three airports, Bristol BRS, Bournemouth BOH, and Teesside MME, saw passenger traffic recover, with more passengers than in 2019.

Smaller UK regional airports with fewer than 3m passengers in 2019 have generally experienced the slowest recoveries particularly those airports where Flybe was a major contributor of traffic prior to its termination in March 2020 including Southampton SOU, Exeter EXT, Cardiff CWL and Norwich NWI. Doncaster DSA closed in November 2022, although there are recent efforts to reopen the airport again.

Thoughts on climate change and impact on aviation

5th November 2021

When forecasting future demand for air travel it is now more important than ever to recognise that the issue of climate change could have a significant impact on the aviation industry.

Aviation emissions have doubled since 1990 to 1 billion tonnes and account for 12% of all transport emissions. In September 2021 IATA announced that its goal was to be net-zero by 2050 despite forecasting that annual traffic will grow by 2.6% CAGR from 4.5 billion passengers in 2019 to 10 billion in 2050.

In the short term, the recovery from Covid-19 will likely have a larger impact than sustainability issues on air travel demand and where the traditional correlation between air transport and GDP growth will be more nuanced.

However, in the next decade decisions made by governments and global corporations will be critical in determining the sustainability of the global economy.

On 3rd November 2021, at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, the UK Chancellor Rishi Sunak announced that 450 companies controlling 40% of global financial assets – equivalent to $130tn (£95tn) – have agreed to commit to limit global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

The aviation industry will need to be resolute in finding and mapping out the effective ways of decarbonising with a scalable increase in the use of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) and developing new technologies including hydrogen and electric fuel cells. IATA’s strategy to achieve net zero emissions requires SAF to contribute two thirds of the reduction in emissions together with carbon off-setting, new aircraft technologies and efficiencies in operations and infrastructure.

While cost of air travel will likely increase in the future, the absolute demand level could be expected to continue to increase. However, policymakers and regulatory authorities will need to ensure that aviation demand can continue to grow sustainably.

If the timeline of measures towards the net-zero path proposed by the aviation industry is delayed, this could see the introduction of demand management policies or regulation in the form of taxation (binary or hypothecation) in the future, which could risk suppressing long-term air travel growth.

Long-term air travel demand forecasting will need to be scenario-based, looking at traffic and destination mix on an airport level driven by the traditional macroeconomic drivers as well as incorporating the dynamic impact of market-based environmental taxes, fuel and other potential cost of implementing the new technologies in the future.

If you like to find out more about our air traffic forecasting services, please contact us.

World Routes Milan 2021

13th October 2021, Jo Hunt, our Associate Director has recently returned from the World Routes Conference in Milan. Here are her thoughts on the conference and the discussions she had.

“It was great to step away from the virtual world and see so many familiar and new faces over the last few days at World Routes in Milan. I enjoyed being able to discuss the industry that we all love and share our experiences over the last 18 months. It has become increasingly clear that there is a real need for airports to now be able to look to the future and understand what the recovery may look like, specifically the pathway back to operating at 2019 levels.”

At Aviation Economics, whilst we recognise that rising carbon costs and environmental taxation is inevitable, the COP26 conference is further proving the need for the industry to set out a credible roadmap to decarbonise aviation. Ensuring we do this will hopefully reduce intervention that could add cost and dampen demand during the Covid-19 recovery period and beyond.

Here at Aviation Economics, we provide short, mid and long term traffic, movement and emissions forecasts and there is an ever-increasing emphasis on the impact of climate change on our industry. Whether required for airport masterplanning, transaction due diligence, refinancing, airport growth strategy or network development, we use both top-down macro-economic and bottom-up forecasting techniques to provide an insight into what the future may look like.

If you’d like to find out more about our services or have a requirement that you would like to discuss, please contact us.

Scheduled airline start-up models – the Low Cost Carrier model is the favourite choice

1st July 2021

As the collapse in demand for air travel has caused market gaps coupled with the availability of aircraft and personnel, we are seeing a significant surge in airline start-ups globally. As is always the case, some are paper airlines that will not actually launch and many that do launch will probably be destined to fail. In this analysis, we look to see what trends there are in the business models being adopted.

The pandemic has created unimagined disruption for airlines around the world, with international border closures and individual country lockdowns also limiting domestic travel.

The drivers of new entry are:

Market opportunities

The failure, restructuring or shrinking of incumbent airlines is creating gaps in the market which new entrants are seeking to exploit as and when travel resumes. From the tables below it can be seen that this is applicable in certain South American countries, Norway, South Africa and Italy where there have been either airline failures of capacity reduction as a result of restructuring.

Balance Sheets

An attraction for investors is that new entrants may be able to gain a financial advantage over incumbents, whose balance sheets are now burdened with debt taken on to sustain liquidity through the pandemic. For example, Norwegian’s business plan has the airline having $20m of debt per aircraft.

Aircraft cost and availability

Pre-pandemic aircraft were in short supply and start-ups were unable to match the cost of ownership achieved by the large LCCs such as easyJet, Ryanair and Wizz in Europe. Lease rates have seen substantial falls across most types and lessors have immediate availability.

Availability of personnel

Aircraft and experienced airline staff, both of which were scarce resources prior to the pandemic, are now widely and inexpensively available.

Suppliers

Many members of the supply chain such as airports, ground handlers, caterers and maintenance providers have all been adversely impacted by lower volumes and will be open to providing attractive commercial deals.

The tables below shows the list of 36 start-ups by region.

Europe start-up airlines

| Airline | Country | Business model | Fleet type | Comment |

| Norse Atlantic | Norway | Long-haul LCC | B787 | Norwegian backfill |

| Air Montenegro | Montenegro | Full service | E-195 | |

| Andorra Airlines | Andorra | Regional | ATR72-500 | |

| HiSky | Moldova | Short-haul LCC | A319 and A320 | |

| Flyr | Norway | Short-haul LCC | B737-800 | Norwegian backfill |

| PLAY | Iceland | Long-haul LCC connector | A321 | WOW backfill |

| Ego Airways | Italy | Domestic regional | E190 | Air Italy and Alitalia backfill |

| Sky Alps | Italy | Domestic regional | Q400 | New markets from Bolzano |

| Bees | Ukraine | Short-haul LCC | B737-800 | Initially operating charter flights |

| flyPop | UK | Long-haul LCC | A330 | Serving UK-India |

| Latitude Hub | Spain | Short-haul LCC | A319 | Partly funded by local government and hoteliers |

| Uep Airways | Spain | Regional | ATR72 | Connecting the Balearic islands |

| Flylili | Romania | TBA | A320 |

Asia start-up airlines

| Airline | Country | Business model | Fleet type | Comment |

| Vietravel | Vietnam | Short-haul LCC | A321 | Domestic and regional |

| Flybig | India | Regional | ATR and Q400 | Based in Indore |

| Greater Bay | Hong Kong | Short-haul LCC | B737-800 | Cathay Dragon backfill |

| AeroK | Korea | Short-haul LCC | A320 | Domestic and regional |

| Super Air Jet | Indonesia | Short-haul LCC | A320 | Links to Lion Air Group |

| OTT Airlines | China | Regional | C919 | China Eastern subsidiary |

| Air Sial | Pakistan | Short-haul LCC | A320 | Domestic |

North America – start-up airlines

| Airline | Country | Business model | Fleet type | Comment |

| Avelo | USA | Short-haul ULCC | B737-800 | Point-to-point on unserved markets |

| Breeze | USA | Short-haul LCC | ERJ and A220 | Point to point, secondary cities |

| Ita | Brazil | Full service | A320 | Latam backfill |

| Nella | Brazil | Regional | ATR-42 | Latam backfill |

| Ecuatoriana | Ecuador | Domestic regional | TBA | Latam backfill |

| Avoris | Dominican Republic | TBA | TBA | |

| JetSmart Peru | Peru | Short-haul LCC | A320 | Backed by Indigo Partners |

Middle East and Africa start-up airlines

| Airline | Country | Business model | Fleet type | Comment |

| LIFT | South Africa | Domestic LCC | A320 | SAA backfill |

| Burundi Airlines | Burundi | Flag carrier | TBA | |

| Ghana Airlines | Ghana | Flag carrier | TBA | |

| Wizz Abu Dhabi | Abu Dhabi | Short-haul LCC | A321NEO | |

| Air Arabia Abu Dhabi | Abu Dhabi | Short-haul LCC | A320 | |

| Royal Zambian Airlines | Zambia | Regional | Emb-120 and Emb-145 | |

| Lone Star Air | Liberia | Full service | ||

| New Saudi airline | Saudi Arabia | Full service | TBA | Backed by sovereign wealth fund |

Oceania start-up airlines

| Airline | Country | Business model | Fleet type | Comment |

| Pacifika | New Zealand | Short-haul LCC | B737-800 | Leisure routes to Cook Islands |

Because many markets have shrunk in size, and may take a number of years to recover, the aircraft operated by many large airlines may now be too large for many routes. On short-haul routes the “standard” aircraft are either B737-800s of A320’s.

Where these large aircraft are too large this leaves a potential gap for airlines operating smaller aircraft that are better suited to current and future market sizes. That said, if demand does recover to previous levels this “opportunity” may be relatively short lived.

Most airline business models are represented by these start-up airlines, even unfashionable models such as long-haul low cost. Short-haul LCCs are perhaps best represented which is understandable given most forecasters belief that leisure recovers quicker than business and short-haul will recover quicker than long-haul.

Author: Tim Coombs

A no-deal Brexit – a doomsday scenario for aviation ?

7th March 2019

Firstly a declaration, I am a staunch remainer. But this article has been written using facts where available, which in some areas are hard to establish in the mist of Brexit uncertainty.

The question is how bad could a no-deal Brexit be for aviation? This article suggests that the answer could be very bad indeed with major potential negative consequences.

The bookmakers are currently giving odds of 5/1 on a no-deal Brexit, a 20% chance that this will be the outcome. As this is a possible outcome I thought it might be interesting to explore what the impact might be on the aviation sector. It is not difficult to see in a no-deal Brexit, that both sides will blaming each other for the failure to agree a deal, and that relations between the UK and the EU member states is going to be anything other than acrimonious. It is based on this premise that this article is written.

Therefore, I have deliberately taken a negative view and presenting a “worst case” scenario because it is probably worthwhile evaluation how bad it might be.

Of course the analysis is open to criticism from Brexiteers, presenting this as just another “Project Fear” point of view? But in a Debate Pack produced for the UK Parliament (Number CDP 2018-0223) published in October 2018 entitled “Effect on the aviation sector of the UK leaving the EU” it was stated that “There have also been concerns about the European Commission’s approach to negotiations on the aviation question and the relationship between the Commission and the UK Government. For example, there were reports in June 2018 that the Commission was “refusing to agree to any back-channel discussions between UK and EU aviation agencies to avert a crisis in the event of a “no-deal” outcome to Brexit”.

What we know so far

The European Union (Withdrawal) Act, which has been in place since June 2018, converts EU law as it stands today into UK domestic law. This will ensure that issues around safety and passenger rights will remain protected.

Presently it is envisaged that travel between the UK-to-EU 27 countries is expected to be visa-fee, although there is the probability that travel permits may be required. The UK has given assurances that EU passport holders can continue to use e-gates.

However UK citizens will have to pay €7 (£6.30) every three years to travel to EU countries, as a consequence of Brexit. The €7 is a fee for theETIAS (European Travel Information and Authorisation System) which is expected to come into force in 2021. The ETIAS system is Europe’s version of the United States’ ESTA.

In the event of a no-deal Brexit, the EU has proposed a temporary, one-year air services arrangement for flights from the UK to the EU from March 29th2019 until March 30th2020. Within this agreement, the European Commission has stated that it will ask UK airlines to adopt a capacity freeze which will not permit any increases in frequencies or the addition of new routes.

Olivier Jankovec, Director General of ACI Europe says that if this was approved it would “ultimately result in the loss of 93,000 new flights and nearly 20 million airport passengers across the UK-EU27 market. UK airports and their communities would be disproportionately affected.”

Quite how this can be enforced when tickets have already been sold is beyond my comprehension, and recent reports suggest that the proposal is unlikely to be enacted. What it does show is that the EU looks set to take a hard line in the event of a no-deal Brexit.

GDP impact

The linkage between GDP and the demand for air travel is well established. Leisure travel demand is driven by consumer confidence, disposable income, the cost and convenience of travel. Business travel is driven by business confidence.

Both consumer and business confidence are correlated to economic growth prospects.

Of huge significance has been the visiting friends and relatives (VFR) market. This market is directly related to social mobility and to migration trends. Increasing labour mobility, both to and from the UK has been a key driver of travel demand. In the past 10 years, 40% of the growth in visitors to the UK has come from visiting friends and relations traffic.

Demand for VFR traffic will be partly dependent on the rights that are offered to EU citizens in the UK and indeed the reciprocal working rights that are available to UK citizens in remaining EU member states.

It is not simply a matter of the new regulatory environment. The outlook for the European aviation industry will be influenced by GDP growth, which most experts expect to be negative.

European carriers will also be impacted by developments in foreign exchange rates (Sterling-Euro, Sterling-USD and Euro-USD) remembering European airlines which are structurally short the USD, the reference currency for fuel, aircraft, engines and spares. Migration patterns are also significant.

David Smith is Economics Editors of The Sunday Times. He summarises the likely economic as follows;

A no-deal Brexit would be very bad for the economy in the short-term and is the worst outcome in the long-term. Leaving a stable trading relationship with our biggest trading partner for a leap into the unknown is just about the most stupid thing a country could do. Yes, other EU countries would be hurt too – when you shoot yourself in the foot, the bullets can ricochet elsewhere – but the damage to this country would be measurably and substantially greater.

David Smith paints a picture of slower economic growth, a sharply lower pound, higher inflation, weak business investment and a loss of foreign direct investment.

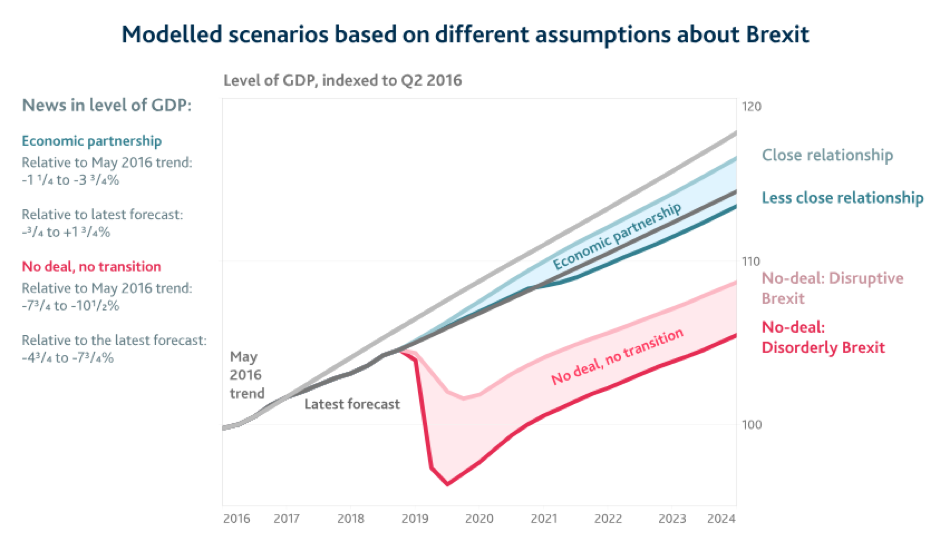

The Bank of England has presented economic scenarios based on the terms under which the UK leaves the EU and are summarised in the graph below.

Source: Bank of England, November 2018

According to the Bank of England, a no-deal Brexit would mean that GDP is between 7¾% and 10½% lower than the May 2016 trend by end2023. Relative to the November 2018 Inflation Report projection, GDP is between 4¾% and 7¾% lower by end-2023. This is accompanied by a rise in unemployment to between 5¾% and 7½%. Inflation in these scenarios then rises to between 4¼% and 6½%.

The key points outlined by the Bank of England in no-deal scenario are that:

- GDP drops 8%

- Sterling falls 25% to below parity with the dollar

- House prices fall 30%

- Commercial property prices plunge 48%

- Unemployment rises to 7.5%

- Inflation accelerates to 6.5%

- BOE benchmark rate rises to 5.5% and averages 4% over 3 years

- Britain goes from net migration to net outflows of people

It is difficult to see anything other than a highly negative impact on the demand for air travel. That is just the impact of macro-economics. In 2009, UK GDP fell by 4% and UK airport passengers fell by 7%. Given the GDP/traffic multiplier that is fundamental to the airline industry an 8% fall in GDP could see a drop in passenger numbers of potentially 12-16%.

Let’s consider a few other aviation specific factors.

Regulation

Airlines, airports and other industry stakeholders have hoped that the UK might remain in the EU Single Aviation market, the multi-national aviation area which fully liberal traffic rights. As MAG Group CEO Charlie Cornish has said, “The best result for the aviation industry would a deal which preserves the liberal flying freedoms and competitive approach to the aviation market that have driven connectivity and economic growth across the continent over the last couple of decades.”

The UK in a Changing Europe stated in a September 2018 paper that:

Brexit in any form will be disruptive for airlines, but failure by the UK and the EU to reach agreement would leave the industry in chaos. Because the sector has its own system of regulation, based on the 1944 Chicago Convention, there is no WTO safety net in aviation. Moreover, although the Chicago system has provided a stable framework for the development of aviation since the second world war, it is unwieldy, difficult to change and restrictive.

Some argue that … fears are exaggerated and that it is in the economic interests of both the UK and the EU to avoid [no-deal]. It is true that contingency measures could be mobilized to retain basic connectivity – for example, the UK could grant access unilaterally – but such steps would merely limit the damage. They would certainly not provide for a continuation of the advanced system that currently exists. A UK-EU air services agreement, as well as UK bilaterals with third countries, would take years to negotiate, as each side aims to secure the best deal for its airlines under uncertain conditions.

The UK is the largest single market for short haul air transport accounting for some 13% of short haul departures in Europe.

A no-deal Brexit creates a significant risk that aviation regulatory structures governing UK air transport could mean that the UK falls back to historical regulatory structures. Before the EU Single Market, to have a UK airline licence, for example, it was necessary to be majority owned and controlled by UK nationals.

UK airlines would need to demonstrate majority UK national ownership and control, as would EU airlines would also need to demonstrate majority EU ownership and control, excluding UK investors.

A reversion to old bilateral agreements will be interesting. The UK has mitigated the risk in arguably the most important and profitable market outside of the EU by signing an Open Skies agreement with the US in November 2018 that that will maintain air links between the countries after the UK leaves the EU. The UK-US market is the largest across the Atlantic, with some 10 million annual passengers representing 29% of all traffic between the USA and Europe in 2017 according to the US Department of Transportation.

It would appear that Norwegian, owned and controlled from Norway, will be treated as having historic rights and will be allowed to continue to fly from the UK to the US. But new entrants from the European Union and related countries hoping to cash in on the richest aviation market in the world would not be granted flying rights.

The outcome of the UK leaving without a deal makes, in my opinion, the probability of the UK falling out of the EU single aviation area without a negotiated bilateral much higher, and therefore open up the reversion to old style regulation would mean that traffic rights could revert and shrink to national airlines of the two countries in each market.

The UK has long had bilateral agreements with many of its important markets, such as the US, which were superseded by EU-third party agreements. The ITC has said that as a result of EU membership UK airlines benefit from 42 Air Services Agreements entered into by the EU with countries inside and outside the EU including the US and China.

Once it has left the EU, the UK will need to have negotiated new agreements with those countries or to have negotiated with the EU and those countries to continue as a party to the agreements as a non-Member State.

In the event of the EU and the UK failing to reach any bilateral agreement, it would appear that the regulatory structure might fall back to the legacy bilateral agreements in place before the establishment of the single market. As the UK had traditionally taken a supportive stance on airline competition many of the bilateral agreements were very liberal.

Whilst I believe that flying will continue after the temporary arrangements end, the continuity thereafter is subject to massive uncertainty, with pan-European operators like Ryanair and Wizz being restricted to services to their home markets of Ireland and Hungary from the UK.

The UK has signed nine other Open Skies agreements. Five of these are to significant aviation markets; Canada, Switzerland, Israel, Morocco and Iceland. The other four are much smaller aviation markets in Central and Eastern Europe; Albania, Georgia, Kosovo and Montenegro.

Brexit campaigners often quoted that the Commonwealth countries represented a major opportunity for the UK in terms of closer economic ties but the UK is yet to conclude a an Open Skies agreement with either Australia or New Zealand. The UK’s existing bilateral with Australia specifically permits the UK to designate carriers from any EU country, which the Australians may want to change in the event of a no-deal Brexit.

The EU has in place or is in negotiation with over 60 countries or regional trade associations regarding aviation agreements, either a “horizontal” or “comprehensive” agreements.

Ownership and control

The EU single market of course relaxed the rules on airline ownership and control within the EU aviation area, and thus paved the way for the creation of Air France-KLM, IAG and the multi-national Lufthansa group and the pan-European operations of Ryanair, easyJet and Wizz. The UK’s stance seems to be that if an airline has a UK Air Operators Certificate (AOC) this allows the airline to function as a UK airline, with no reference to the nationality of the shareholders. Whether the third parties that the UK has to negotiate with, the EU and other countries elsewhere, will accept this must be in considerable doubt.

easyJet was the first mover in establishing an EU AOC alongside its existing UK and Swiss AOCs. With the dual EU and UK nationality of its founder, Stelios Haji-Ioannou leaves easyJet better placed to face potential regulatory issues over ownership and control.

The ownership structures of IAG’s EU airlines, as well as Wizz, and Ryanair would be in question. These Pan European businesses would defend traffic rights by demerging into UK and EU businesses. Yet, with a less stable regulatory regime, the risks of establishing UK businesses would be greater for the Pan European businesses. In this situation there may be greater need to demonstrate genuine UK ownership and control of UK.

The ownership regulations leaves IAG facing structural challenges that could require the demerger of BA from the EU operating companies. IAG has been reluctant to publically disclose its national ownership structure, but it is thought that IAG would likely fall below majority EU ownership requirements.

IAG also faces issues regarding traffic rights such as the Belfast based flying of Aer Lingus and the UK-Italy operated by Vueling.

As Andrew Lobbenberg, the airline analyst at HSBC Banks says;-

“We see IAG particularly vulnerable in the context of ownership and control given that post Brexit it would not be owned or controlled by EU nationals. We consider the company’s focus on the domicile of the Holding company and the scale of its businesses as an irrelevant appeal to realpolitik. Moreover, we see the Iberia and BA trust structures as irrelevant in the context of meeting the requirement for majority EU ownership and control. We see IAG’s best contingency plan lying in Qatar Airways somehow re-domiciling its 20% stake into the EU, but this would be complex.”

For Ryanair and Wizz they face the possibility of needing to establish independently owned UK businesses, to defend traffic rights to countries other than their home countries.

In a no-deal scenario I foresee complex ownership and control challenges for airlines including Ryanair, Wizz and IAG. Air France-KLM’s investment into Virgin Atlantic could also be untenable. It is perhaps Lufthansa, among the European majors that has least regulatory risk regarding Brexit.

Legal challenges could be mounted by regulators or perhaps by airlines that want to disrupt the operations of their competition.in several of our considered scenarios.

On both a Europe wide basis, as well as to and from the UK, the overwhelming majority of services of both Ryanair and Wizz are dependent on the liberal seventh freedom traffic rights of the single market. For example, should operations fall back to the historical bilateral environment, Wizz, as a Hungarian airline would have been able to fly exclusively to and from Hungary. In 2017, 88% of Wizz’s services to and from the UK would not be permitted.

Safety

Currently the UK benefits from being a member of the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) which covers safety issues across all Member States. A no-deal Brexit puts the UK’s membership in doubt.

In a March 2018 report the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Select Committee set out the potential consequences of a UK exit from EASA:

If the UK is to make a managed departure from EASA, it would require a transition period in which special arrangements are made with the EASA, the US Federal Aviation Authority and other global regulators. The Civil Aviation Authority would need to undergo a major investment and recruitment programme if it is to take over the functions of EASA at some point in the future, and Bilateral Aviation Safety Agreements with mutual recognition agreements would need to be negotiated with the EU, US and other major markets. Given the complexities involved, this transition may need to last beyond the two years that the Prime Minister has said is likely to be appropriate for the economy-wide implementation period. This disruptive and costly process is unlikely to result in any significant divergence in regulation.

Conclusion

A no-deal Brexit would appear to be a potential calamity for the aviation industry. The demand for air travel will be adversely affected by a major contraction of the UK economy and the risk of contagion on the economies of the remaining EU member states. Leisure travel seems most at risk being impacted by a fall in the value of Sterling, lower disposable incomes, higher levels of unemployment, falling house prices etc.. Softer issues will also have a negative impact, consumer group Which are predicting five hour queues at immigration at Spanish airports such as Alicante and Tenerife, higher data roaming charges, more complicated and costly procedures for car hire etc..

And then there are also the issues around the future regulatory structures around Air Service Agreements and bilaterals and the complexities of ownership and control. The title I chose for this article uses the word “Doomsday” whose definition is, according to the Macmillan dictionary, “an extremely serious or dangerous situation that could end in death or destruction”. Perhaps using the word “Doomsday” is a little strong…………………but then again perhaps not.

Author: Tim Coombs

UK Votes to Pay More in Airport Charges if No Brexit Deal

6th November 2018

Windfall for airports, passengers to pay the price if air routes from the UK are re-classified as being international rather than Intra-EU

Looking back at the somewhat depressing and inept Brexit debates back in 2016, the subject of airport charges wasn’t discussed in any great detail. No ‘battle buses’ declaring that every week UK citizens might be paying millions more to Europe’s airports instead of on the National Health Service, no billboards with made-up numbers to scare the population into voting one way or the other. Did no-one consider that airport charges could even be a factor in possible future Brexit negotiations?

In March 2019, the UK will cease to become a member of the EU. At the moment, the precise nature of the departure isn’t known, so the UK may still become Canada, Norway, or an international outcast subject to WTO rules on trade if ‘no deal’ comes to pass. The UK will still be a European country, but in spite of the geography, the UK’s changing relationship with the EU will have a bearing on the airport charges UK passengers pay to use some of Europe’s airports and that depends on how the airports categorise flights departing for the UK.

If flights to the UK change status, airport fees will increase generating a ‘Brexit windfall’

Many airports across the continent differentiate their departing passenger charges depending upon the flight destination. Domestic charges are usually the cheapest, followed by Schengen (if applicable), then come charges for EU destinations, and finally International charges, which usually carry the highest rate. In many cases, nations in the EEA grouping (and often Switzerland) are lumped together with EU nations, enabling them to benefit from charges that are cheaper than if they were deemed international destinations.

In the world of airport charges, then, the status of the UK after March next year matters; if the UK is treated like Norway, then in most countries UK passengers will see no change in their airport charges. However, if the UK is seen as being an ‘international’ destination, then many airports across Europe will be able to charge a higher fee for passengers heading to the UK than they do today. in doing so, they will see a ‘Brexit windfall’, as UK passengers will move from paying EU charges to the more expensive international charges. In fairness to the airports concerned, this would be a cost of the UK’s own making; none of the airports concerned is trying to penalise UK passengers, nor are they introducing ‘new’ charges – it’s just a consequence of the UK leaving the EU club.

Taking the 2018 schedule as a guide, we can estimate how expensive a ‘no deal’ Brexit might be to UK passengers. There will of course be a corresponding cost increase for European passengers coming to the UK, but for the purposes of this analysis, we’ll concentrate on UK originating passengers only, as it was their choice to leave the EU.

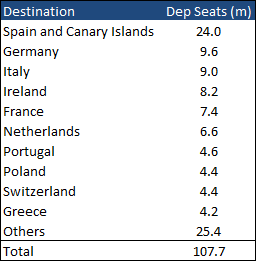

Over 60% of all scheduled UK air passengers have somewhere in Europe as their final destination, making it the most popular for both business and leisure travellers. As the table below shows, there will likely be over 107 million scheduled seats departing the UK for Europe in 2018. Between them, British Airways, EasyJet and Ryanair account for 56% of these seats, making those airlines more interested than most in how the Brexit negotiations unfold.

UK-Europe scheduled seat capacity by destination country, full-year 2018

Source: RDCApex.com, OAG

Annual passenger numbers are not yet available for 2018, but assuming that the remainder of the year continues without significant hiccups, it’s reasonable to assume that UK-Europe passenger numbers at prevailing load factors will be of the order of 92m come the end of the year. Some of these passengers will be inbound visitors to the UK, but historically most passengers on UK-Europe services originate in the UK. Assuming 80% are flying outbound, we estimate 74m UK passengers will have flown to European destinations by the end of 2018. Most of them will be point-to-point passengers, but we have made allowances for onward connecting passengers at key hub airports like Paris CDG and Frankfurt so as not to overstate the charges incurred.

The biggest winners are in five countries – with Spain the biggest

Not all airports and countries differentiate their passenger charges in the same way, so even if no Brexit deal is done, becoming an international passenger at many airports in many countries won’t change the charges paid. By analysing airports on a country-by-country basis, it becomes clear which airports will see no change, and which will benefit from the Brexit windfall.

Five countries stand out as having the most to gain from a no deal Brexit, as either all, or nearly all, of their airports have higher charges for international passengers than they do for EU passengers. Although five is only a modest proportion of EU countries, these countries are unfortunately all in the top seven most popular destinations for UK passengers, including filling the top three places. They are flagged below.

There are the odd one or two airports in other countries that will also benefit, but these five countries are by far the most significant for UK passengers.

Airport winners – Top 20 biggest destinations

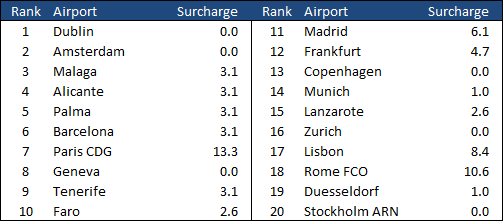

The two most popular EU destinations from the UK are Dublin and Amsterdam. Neither of these airports differentiate their EU and international passenger charges, so passengers can continue to fly to these destinations with no additional costs. Unfortunately, 14 of the rest of the top 20 have higher charges for international passengers than they do for EU passengers. The table below summarises these additional charges per passenger for the 20 most popular UK-Europe scheduled routes.

Per passenger surcharge for International passengers, EUR per pax

The popularity of the Iberian Peninsula is much in evidence, accounting for nine of the top 20 destinations, and all have higher charges. Just six of the top 20 have no charge differential, while the highest increases in charges are at Paris, Rome and Lisbon. The seat of the EU, Brussels, comes in at number 33 on the list, and in the spirit of continued European cooperation, will be no more expensive for UK passengers after Brexit than it is now.

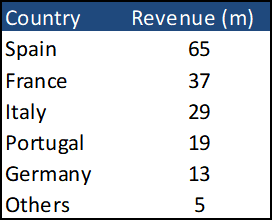

A €65m windfall for Spanish airports, while UK passengers pay €170m more

Using the estimated scheduled passenger numbers for 2018 and the change in charges at each European airport, we can estimate how much extra UK passengers could be paying to Europe’s airports if the UK drops out of the EU with no trade deal – or if Europe’s airports choose to re-classify the UK as an international rather than EU destination. Our estimates suggest that the extra cost of airport charges to UK passengers would be around EUR170m per year. Virtually all of this cost is concentrated in the top five countries flagged previously;

Increase in UK passenger charges revenue by country, EUR

80 airports are better off and 30 will see an increase of over a million

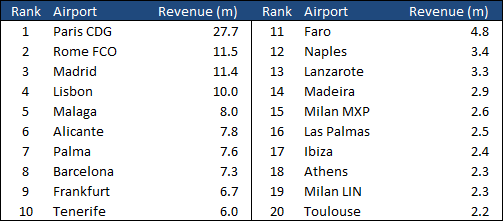

There are roughly 80 airports across Europe that will see a Brexit windfall, with over 30 of those seeing an income increase in excess of EUR 1 million. The top 20 beneficiaries, together with their projected increase in income, are shown in the following table;

Increase in UK passenger charges revenue by airport, EUR millions

Paris CDG would be by far the biggest beneficiary of a Brexit windfall, attracting 16% of all of the additional charges that might be paid by UK passengers. Rome, Madrid and Lisbon together account for another 20% of the total additional charges as European capitals fill the top four places in the list.

Forward bookings and airlines beware

Next summer seems an awfully long way off, yet there are already people out there booking tickets for flights in April 2019 and beyond. For airlines selling seats from the UK into Paris, Rome or Lisbon in particular, a Brexit deal would clearly be advantageous, otherwise those routes may not be quite as profitable as they’d hoped for. Likewise, if an airline network is thick with routes taking UK holiday makers to Spain, they may end up paying a few more Euros per passenger in airport charges than they’d anticipated.

So, while the Brexit debate and its ramifications may seem very big and far away, the reality is that a no deal outcome could affect sales that have already been made. Every ticket sold before the end of March 2019 on routes from the UK to over 80 European airports could be mispricing the airport charges element of the price, potentially leaving airlines with a bill of millions of Euros.

For every ticket sold after the end of March 2019 to these destinations, the correct pricing of the airport-related charges will leave UK passengers with an additional bill of around 170 million Euros